Book Notes and Main Takeaways: “Event Storming” by Alberto Brandolini

alberto-brandolini event-storming domain driven design highlights Product and Tech book-highlights

(LM → my personal comments)

General quotes

It turns out that the steps are awkward. The software is imposing a couple of extra process steps to guarantee consistency of the internal data structure, but this approach is unnaturally pushing complexity outside the software, forcing users to do extra manual activities on paper and phone.

Finding a solution won’t be as easy as spotting the problem. And the blocker is only the visible symptom, not the root cause. But choosing the right problem to solve is a valuable result and we achieved it quickly.

Even if we established a clear link between the main process blocker and a possible solution, putting it to work is not only a technical issue: permissions needed to be granted, and roles and responsibilities in the organization around that step needed to be redesigned to overcome the current block.

Despite the initial assumption that software was the most critical part, it turned out that the solution was mostly politics. And when it comes to politics, transitions usually take more than expected, and they’re never linear or black-and-white.

we start introducing more rigor in our process by introducing Commands representing user intentions/actions/decisions (they are blue stickies where we write something like Place Order or Send Invitation), and Actors (little yellow stickies) for specific user categories.

Read models are emerging as tools to support the decision-making process happening in the user’s brain

Only a few places still look like CRUDs, but most of the business is described in terms of Events flowing in the system. -> And it feels so right.

Domain events may come from:

- result of a command

- result of a domain event triggered by an external system (eg. paypal)

- result of time passing (eg. paymentTermsExpired)

- result of another event

Silos minimize the learning newcomers need to start contributing to the company business.

This is the fundamental evolutionary advantage of Silos: they allow us not to spend much time explaining our organization to newcomers. Somebody is going to say something like: “That’s all you need to know!” and the new hire is now ready to deliver value, with no possible excuses.

Silos promote local optimizations. It’s easier to gather consensus (more about it later) around issues and agree on local improvements than to find a cross-team or cross-department agreement.

we need to define some goals and targets sounds like common sense or a tautology. Yet, linking salary bonuses to reaching given goals isn’t necessarily obvious or even a great idea. Over justification - replacing the existing intrinsic motivation with an extrinsic one, a prize, or a sum of money - has the nasty effect of killing the original motivation. It does work with dogs, but it’s already wrong with kids. If you’re working with adults, maybe you should be looking for something more sophisticated.

Organizations are made of human beings and shaped by their decisions.

We’re biased to add, not to remove It turns out there is a strong bias towards adding things instead of removing them

We’re given a small lego structure, and we assume there must be a reason for this shape. Nobody mentioned it, but well …let’s make sure we’re not making mistakes or irritating anyone.

Now, forget easy experimental challenges with lego bricks and think about processes and rules in your organization. Many people will complain about them, but very few people will have the guts to break them or even take the initiative to change them unless they’re pretty sure there won’t be consequences.

LM: people are so afraid to refactor old code, so complexity only grows and exponentially

The natural bias towards adding is strong and pervasive. We can affect organization agreements, but software development, law-making, and city evolution follow similar growth anti-patterns.

LM: software developers that were not exposed to the cost of their “additions” in their work experience (in my view, most developers who never worked at an early stage startup) will just add another database, add another messaging system, add another framework. They’ve never paid the price of maintaining those things because they changed teams, or because they had a devops team to manage the infrastructure for them. The one with narrow views, not even realize they are paying the price because they are just doing tickets, so they don’t realize the work they are doing now is a consequence from their decision a couple of months back.

I suspect the reason has to do with confidence: you’re not taking many risks adding one more piece to the puzzle. Removing one piece instead requires being aware of the impact of your choices on a larger ecosystem. When this awareness is hard to achieve - like in complex artifacts, siloed organizations, or untested legacy software - you enter the realm of risk-taking… or simply stay out of it.

Facilitation around critical decisions is necessary and challenging. Unstructured discussion can lead to half-hearted commitment, an illusion of consensus, or - worse - the feeling of being tricked into someone else’s agenda.

Software development is a learning process, working code is a side effect

LM: and AI will take care of the latter.

It’s not the typing, it’s the understanding that matters. However, once you acknowledge this, a whole world of inconsistencies starts unfolding.

What is the value of code written on time, and on budget by someone who doesn’t understand the problem?

LM: OMG this is sooo true. The answers is “negative value”. Just added complexity without any gains.

Just measuring deliverables is a lot easier. But this oversimplification is poisonous. The value for the company is not in the software itself, it’s in the company ability to leverage the software in order to deliver value.

LM: hence why project managers are mostly unnecessary or they destroy value according to Marty Cagan. They widen the gap between value and software.

Software doesn’t work like that. Misunderstandings aren’t funny, they’re more likely mistakes that could cost a lot of money, or even human lives.

Coding and ambiguity don’t play along very well. Coding is actually the moment when ambiguities are discovered, in the form of a compile error, an unexpected behavior, or a bug. Conversations tolerate ambiguities, but Coding won’t forgive them.

Checklist: How many people understand your system?

- Nobody –> you’re probably screwed

- Only one person –> you’re probably even more screwed, but it’s harder to admit.

- A few people are reasonably competent on the whole –> safer.

- Everybody knows the whole story –> just lovely.

iterative development is expensive. It is the best approach for developing software in very complex, and lean-demanding domains. However, the initial starting point matters, a lot. A big refactoring will cost a lot more than iterative fine tuning (think splitting a database, vs renaming a variable). So I’ll do everything possible to start iterating from the most reasonable starting point.

Among all approaches to software development, Domain-Driven Design is the only one that focused on language as the key tool for a deep understanding of a given domain’s complexity.

Domain-Driven Design doesn’t assume consistency of the different areas of expertises. In fact, it states that consistency can only be achieved at a model level, and that this model can’t be large.

LM: example: a “product” entity can have different purposes, properties and names depending of the domain: for warehouse, it’s called inventory.

When modeling large scale system, we shouldn’t aim for a large “enterprise model”. That’s an attractor for ambiguities and contradictions. Instead we should aim for 2 things:

- multiple, relatively small models with a high degree of semantic consistency,

- a way to make those interdependent models work together.

A small, strongly semantically consistent model is called Bounded Context in Domain-Driven Design -> a portion of the model which we must keep ambiguity free. Every word in the model has exactly that precise meaning.

The event storming approach:

- See the system as a whole.

- Find a problem worth solving.

- Gather the best immediately available information.

- Start implementing a solution from the best possible starting point.

This is what we do in EventStorming: we gather the best available brains for the job and we collaboratively build a model of a very complex problem space.

Event storming session guide

The action will take place in phases of increasing complexity. We’ll keep things easy at the beginning, adding more details as long as people are getting confidence with the format. We’ll leverage the idea of incremental notation to keep the workshop in a perennial “Goldilocks state”: it has to be not too challenging, not too easy, just right!

Set the context / intro

- “short informal presentation round, to discover everyone’s background, attitude, and goals, and to allow everyone to introduce themselves.”

- set the goal: “We are going to explore the business process as a whole by placing all the relevant events along a timeline. We’ll highlight ideas, risks, and opportunities along the way.”

- set the expectation: “the workshop is going to be chaotic, mostly stand-up, it’s going to feel awkward at given moments, and this is all expected.”

- maybe: “ run a time-boxed warm-up exercise, by collectively modeling a well-known story (Cinderella is one of the favorites) so that participants get familiar with the basics of the method, without worrying of their problem space first.”

Steps

- key (domain) events in orange sticky notes, using a verb in past tense, and to place them along a timeline. eg: “Item added to cart”

- has to be relevant to domain experts

- ps. “a different phrasing, using an active verbal form like Place Order instead of Order Placed is a minor issue at this moment, while using phase names like Registration, Enrollment or User Acquisition will filter out too many details from the model. Some people are tempted not to dig deeper into those phases, but we do care about the details.”

- break committees circles as they will hide exactly the contradictions we want to explore.

- Different actors might have created different locally ordered clusters in a disordered whole and thats ok

- cool down. encourage and take a break

- enforce/sort a timeline

- “This is when the discussion gets heated: local sequences - “this is how it works in my own silo” - have to be merged with somebody else’s view on the same event. And the whole thing needs to make sense. Inconsistencies start to get visible, and once they’re visible …somebody will talk about them!”

- strategies

- mark the pivotal events

- create swim lanes for parallel processes

- mark the temporal milestones (eg. 1 year before/6 months before/3 months before)

- group events into chapters and sort the chapters

- introduce time-triggered events (eg. “end of the month” marked with a little calendar icon to indicate it’s time based)

- introduce recurring events

- capture every warning signs (eg. “and this is where everything screws up”, “this takes forever”) in purple sticky notes. Also used for “discussions” and “questions”

- “While everybody is busy trying to make sense of the orange sticky notes, the facilitator should look for places where the discussion is getting hot and marking them with a purple sticky note.”

- “I like to leave HotSpots for the facilitator during this phase. An explicit call for problems too early in the workshop can create a flood of problems with a very low signal to noise ratio.”

- “HotSpots capture comments and remarks about issues in the narrative, and I am expecting to find quite a few of them. In fact, EventStorming provides a safer environment for going hard on the problem (which is now visible on the wall) while being soft on the people.”

- add

commandsrepresenting user intentions/actions/decisions andactorsfor specific user categories- “I prefer to use the term people instead of actors, users, roles or personas since it’s not tied to any specific system modeling approach.”

- “This fuzziness will lead to a wide range of possible representations, from the most generic User to ultra-fine grained users like John and Amy, passing through all the possible variations of New Customer versus Returning Customer and so on.”

- “Adding significant people adds more clarity, but the goal is to trigger some insightful conversation: wherever the behavior depends on a different type of user, wherever special actions need to be taken, and so on. Don’t be worried if these conversations are disrupting your current model. This is a good thing!”

- add External system

- ”external system is whatever we can put the blame on”

- “It’s also funny to see developer’s behavior over a piece of legacy software: sometimes it’s external, sometimes this piece of software is us. Little language nuances will tell a lot about the real ownership, and the level of commitment or disengagement with software components.”

- “It is a good sign if your storytelling is bumpy and continuously forcing you to add more events. Your brain pain means that it’s actually working.”

- add problems (purple) and opportunities/ideas (green)

- arrow voting

- “Any workshop participant can cast two votes.”

- “I tend to use the words “most important problem to solve”, knowing that ‘important’ is a subjective term. ”

- add read models (green) -> the data needed in order to make that decision

user categoriesmight evolve to acollection of personasif their motivations are different

- add side effects or policies (automated or manual) - “reactive logic that takes place right after an event and triggers one or more commands somewhere else”

- add aggregates (see Modeling aggregates section Below)

LM: your workshop might not need all those steps and the facilitator should feel what’s most important to help the overall clarity of the system to improve to all participants. In my experience with online Event storming sessions, just adding events and enforcing a timeline already generates a ton of value and this can take many 1/2 hour sessions.

Some discussions cannot be solved during the workshop. And narrowing the focus to one single issue might not be the best use of everybody else’s time. When a conversation is getting non-conclusive, I mark it with a Hot Spot (signaling that it won’t be forgotten) and move on. On the other hand, some discussions are interesting for everybody, and the workshop might be the one chance in a lifetime to get a long-awaited clarification.

Reverse Narrative is a powerful tool to enforce system consistency. Even if we think we’re done with forward exploration, we usually discover a relevant portion of the system (around 30-40%) that was buried under the optimistic thinking. -> Pick an event from the end of the flow, then look for the events that made it possible. The event must be consistent: it has to be the direct consequence of previous events with no magic gaps in between.

Big Picture workshop

- Invitations: make sure you have the right people in the room, the ones who know and the ones who care.

- Room Setup: provide enough maneuvering space for your little crowd to work on the modeling surface in the smoothest possible way. Don’t forget the basics: food, light, and fresh air.

- Kick-off: make sure that everybody feels aligned with the workshop goals, possible warm-up round.

- Chaotic Exploration: everybody frantically starts adding the domain events they’re aware of, to the modeling surface. Some interesting conversations can pop up, but people will mostly work in a quiet, massively parallel, mode.

- Enforce the timeline: let’s make sense of the big model. Restricting the flow to a single timeline forces people to have the conversation they avoided until now. The structure will emerge from the common archetypes. More events will be added, but most of the work is moving events to achieve a meaningful structure. This is also the moment where Hot Spots appear.

- People and Systems: which are the key roles in our business flow? Making people and systems evident, we are reasonably sure that if there are impediments to the flow, they are visible to everyone else in the room. This round is also another hot spot detonator: once everything is visible, people can’t stop commenting.

- Explicit Walk-through: different narrators will take the lead in different portions of the system, describing the visible behavior and accepting the challenge of other participants.

- Reverse Narrative: if we’re confident with the overall flow, we can ask people to think in reverse temporal order, or in strict causal order if you prefer. Quite a few events get added to the model, and the original flow becomes a lot more sophisticated than the original one.

- Problems and Opportunities: time to allow everyone in the room to state their opinion and ideas about the current flow.

- Pick the right problem: once everything is visible and marked with a hot spot, it may make sense to choose the most important problem(s) to solve. Sometimes you have clear consensus; sometimes you’ll vote and have surprises.

- Wrapping up: take the final pictures, manage the closing conversations, do the needed clean-up, or postpone it if you can. (meaning, leave the board visible so it triggers conversations in the next days)

Optional Steps

- Add value created/destroyed

- allow many types of value, no just monetary: time, safety, reputation, stress

- “Sometimes talking about value isn’t as obvious as expected. Failing to find a real reason why users should perform a given action can quietly kill a start-up idea before wasting millions. Or at least suggest us to run a cheap experiment to validate the assumption, and eventually kill the initiative. As sad as it may sound, it’s not nearly as bad as finding yourself trapped inside a long-living organization that has lost its purpose.

- “Playing with multiple value currencies can help some reflections about what is the real type of value that our organization is delivering and try to optimize accordingly. Instead of focusing on the trivial revenues, you may discover yourself improving revenues by focusing somewhere else, like improving simplicity or speed, or even good mood.”

LM: focusing on revenue and sales goals can in fact decrease the long term value for the company, because it’s harder to think long term when you focus on revenue, but it’s easier when you focus on customer value. -> in the long term, customer value === company value

Domain boundaries

Now I consider “getting the boundaries right” the single design decision with the most significant impact over the entire life of a software project. Sharing a concept that shouldn’t be shared or that generates unnecessary overlapping between different domains will have consequences spanning throughout the whole socio-technical stack.

Ideally, a bounded context should contain a model tailored around a specific purpose: the perfectly shaped tool for one specific job, no trade-offs.

Whenever we realize a different purpose is emerging, we should give a chance to a new model, fitting the new purpose, and then find the best way to allow the two models interact.

It’s our job as software architects to discover boundaries in our domain, and this will be more an investigation on a crime scene than a tick-the-checkboxes conversation.

During a Big Picture Event storming, It’s usually a good idea to resist the temptation to resolve those duplicates and find and agree on a single wording choice. Different wording may refer to different perspectives on the same event, hinting that this might be relevant in more than one Bounded Context, or that the two or more events aren’t the same thing.

boundary events are also the ones with different conflicting wordings. Here is where the perception of bounded contexts usually overlaps. A key recommendation here is that you don’t have to agree on the language! There’s much more to discover by making disagreements visible.

Moreover, keep in mind that when two models are interacting, there are usually three models involved: the internal models of the two bounded contexts and the communication model used to exchange information between them.

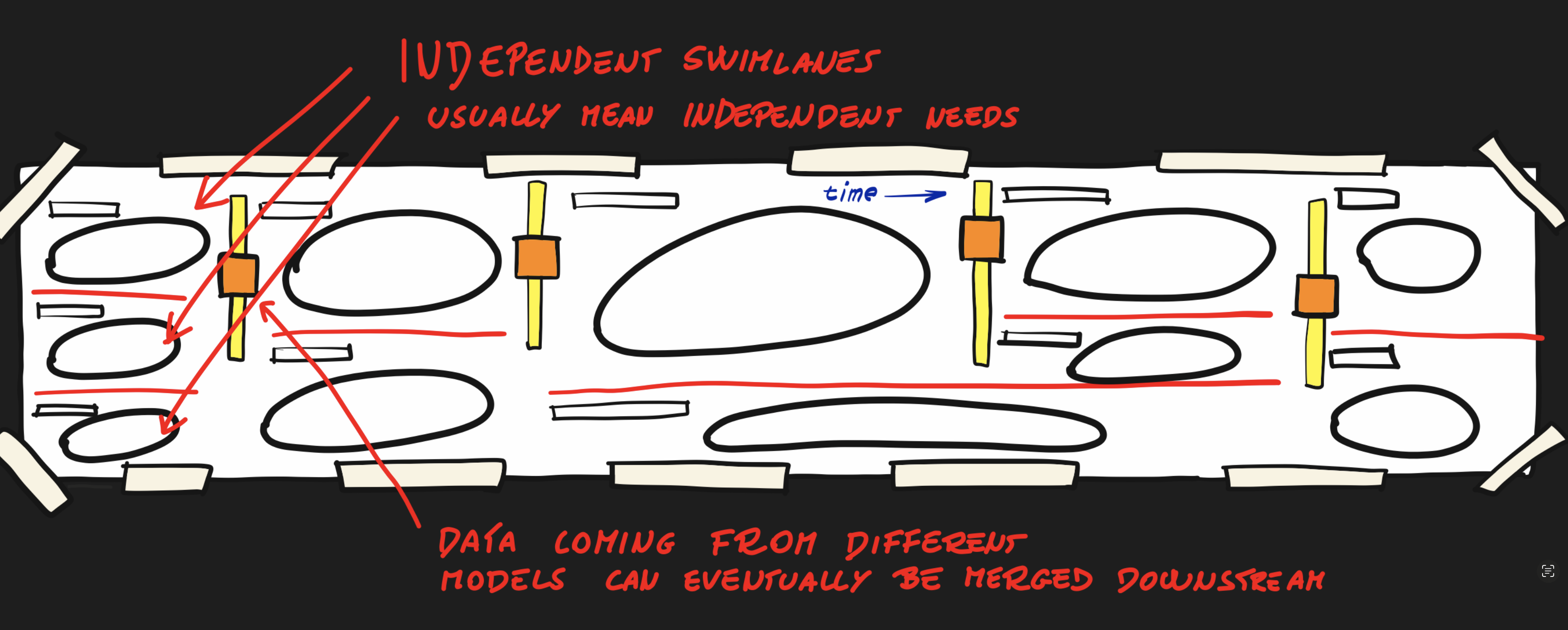

In general, different phases usually mean different problems, which usually leads to different models.

Heuristics for finding/determining bounded contexts:

- look at business phases (pivotal events)

- “In general, different phases usually mean different problems, which usually leads to different models.”

- look at the swim lanes

- look at the people/actors

- look at the humans in the room

- look at the body language

- different needs mean different models.

- listen to the actual language

- “The thing has probably the same name, and needs to have some data in common between the different models …but the models are different!”

- “Looking at verbs provides much more consistency around one specific purpose.”

Facilitator Checklist

- Postpone precision

- Unlimited Modeling Resources

- Have more than enough markers

- Visible legend

- Capture Definitions of mysterious term or acronym of the organization domain (Yellow stick note)

- don’t allow people to draw arrows during the “enforce a timeline” phase

The model is basically two things

- an excuse to trigger the right conversation with the right people,

- a tool to improve the quality of the emerging conversation.

Even if getting finally to the big picture felt exhausting, the real outcome is that you’ve been there, had the discussion and created the model. Don’t fall too much in love with it: the model is still wrong.

Remote Workshop notes

- Half day session (no full day session due to Zoom Fatigue + timezone differences)

- When looking for bounded contexts

- Frames can help highlight candidate bounded contexts and also make them portable.

- I use larger stickies for pivotal events.

- We can use arrows to connect an event to listening subsystems, making the event fan-out even more visible.

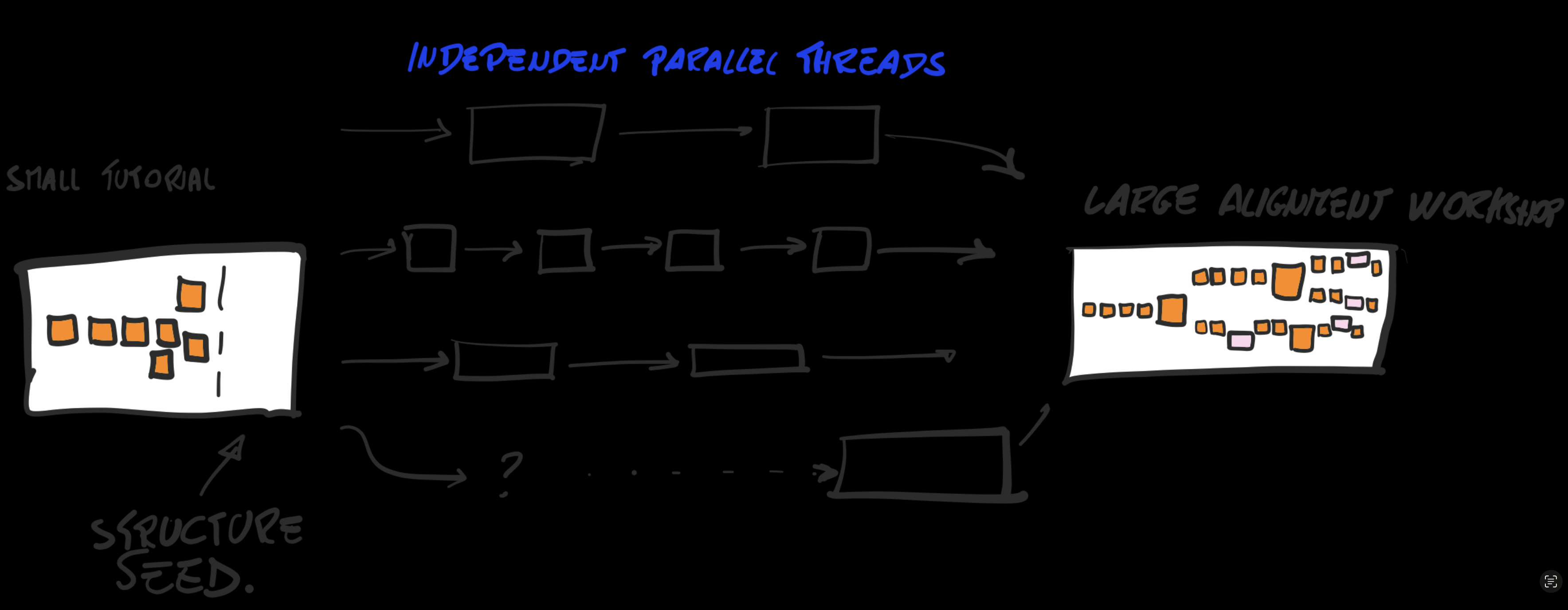

- You can split the workshop in smaller parallel threads, provided an expert is available for facilitating

- Seeding a skeleton structure to facilitating global ordering before starting: just a few Events (possible candidates to be Pivotal Events) and/or Frames to provide some structure before the activity starts.

- optional: use different colors as personal signatures. When narrating the story, turn orange all events that has been enunciated by the narrator and validated by the audience.

- mental model: every step is an experiment. Make copies of the whole model on each step so you can easily go back if a given step is not making the model better.

- Make interests explicit

- on top of the Validated Narrative ask people to place their name/picture/avatar near the arear of interest

- Main recipe/tools/steps are still valid, with some tweaks

- pre-seed the board with some possible candidates to be Pivotal events

- colored brain dump -> let people add what the know to the board

- frame sorting -> sort/merge/split the colored sections

- Select Pivotal Events and connect it to interested downstream frames

- Add People and System

- create a validated narrative

- Explore

- playing with value

- explicit interests

- problems and opportunities -> arrow voting

Process Modeling (a given feature/use case)

We’re expecting processes to start from a given trigger (usually a Command or an external Event), and to finish with a combination of Events and Read Models.

I tend to be really strict in the implementation of the color grammar when it comes to policies because there is always a business decision between an event and the reaction. Sometimes the underlying decision is too obvious to be noticed; the mandatory lilac is just there to force your modeling team to think.

Policies represent business decisions, organization reactions to given events, and our stickies can represent different stages of maturity.

Policies tend to be the first thing that needs to change when the business context changes. Policies are the flexible glue between the other building blocks of business processes.

The interesting bit here is that policies is where people lie. Discovering the real implementation of an existing policy is an investigation game: people will not tell you the real story at first attempt.

In EventStorming I explore Read Models starting from the decision: the decision needs data; hence, the data needs to be available, and I capture it in a read model.

avoid sequencing read models -> Some implementation need sequences, and the sequence matters, but many times, fetching data is not a process step: it’s a piece of one possible solution leaking into the problem space.

“Policies as placeholders for a mandatory conversation.”

“Hotspots as a tool from smart procrastination.”

expecting a linear process model is an illusion -> it’s normal to have a continuous explosion of branches/alternatives -> As you can only solve one problem at a time, use hotspots to make the paths you’re not exploring now visible, finish the exploration of the most important branch, then comeback and start again from the next most important branch.

Rush to the goal strategy -> Model the process as a straight line really fast (it won’t reflect reality). When speaking out loud, capture all objections with Hotspots and only then start exploring the them.

If we zoom into business transactions, we’ll discover that they’re never atomic but they’re rather a sequence of states which are somewhat inconsistent.

Once released in production, Domain Events have a very annoying cost of update, due to their high number of potential listeners. Renaming a domain event in order to increase precision, might require many other software components to be updated. As every Domain-Driven Design practitioner knows very well, naming is an incredibly hard problem, so anticipating the mess, while the model is still only paper is probably a good idea.

Modeling Aggregates

In Domain-Driven Design, Aggregates are defined as units of transactional consistency. They are groups of objects whose state can change, but that should always expose some consistency as a whole.

- “there would be no way to have inconsistent reads while accessing different portions of the aggregate”

- “If developers can play by these rules, they can then decide whether to calculate values on the fly, whenever someone is accessing it or upon change and then storing the result in some variable” eg. shopping cart total is the sum of prices of all items in the shopping cart

- Aggregates are in fact an elegant way to define a behavioral contract with a given class, providing freedom of implementation on the internals. Some may call it encapsulation. ;-)

- “data to be displayed to a user in order to make a decision” will be a Read Model. Aggregates are something else, but we have to be aware of this vicious temptation of superimposing what we need to see on the screen on the internal structure of our model.

LM: aggregate === “units of consistent behavior”

Main takeaways

- aggregates as units of consistent behavior

- we don’t need agreement on language through the whole org, just inside each bounded context and at the communication layer. There’s always 3 models: mine, yours and our API/events.

- silos have their purpose and are necessary in bigger organizations. The problem is when the complexity of what it’s in your silo leaks outside of it, usually due to poorly draw boundaries.

- awesome quote to summarize software development: “Software development is a learning process, working code is a side effect”

Learnings from participating in Event Storming Sessions

- This is a phenomenal tool, specially for creating safe knowledge sharing space. It makes most important problems visible!

- Things that I saw as super important

- having an experienced facilitator to keep things flowing and marking the possible hotspots

- having some pivotal events before starting to minimize the organizing effort later

- different wording for the same events are a super clear indication of different bounded contexts -> this facilitates a lot finding your bounded contexts

- when discussing events at the boundaries of each bounded context, you don’t need to agree on language. There is a ton of value in just making this disagreement visible.

If you're a software engineer working on product teams and found this useful, you might enjoy my book Your Code is Not the Most Important Thing in the World — it's all about understanding value creation, making value-driven trade-offs, communicating with excellence and knowing how to navigate organizations.

Learn more on the book page